AI & Human Rights

AI is reshaping business, but addressing its human rights risks is key to ethical and sustainable adoption.

By Loading

.2e81242a.png&w=256&q=75)

Download the report: AI & Human Rights

Executive Summary

- Artificial intelligence (AI)1 is increasingly ubiquitous in business processes, offering tremendous potential productivity gains across all sectors and functions—from automating rote tasks to enhancing customer service, marketing, cybersecurity, supply chain optimization, and strategic decision-making. These commercial advantages, however, come with human rights risks and opportunities for workers, customers, and others affected by AI deployment. Effective and resilient corporate AI strategy ideally integrates potential human rights2 impacts to navigate a suite of legal, investor, and brand risks. This article provides a high-level overview of potentially relevant human rights impacts for companies to consider when deploying AI.

Insight

As AI can process and synthesize large amounts of data and enhance effective decision-making, its positive impacts on human rights are significant. For instance, it can be used to rapidly identify human rights violations and indicators of human rights violations, whether through processing data related to recruitment, calculating pay through a living wage analysis, predicting election-related violence, or identifying possible privacy breaches. This allows for more effective violation prevention strategies and the ability to more rapidly address actual human rights harms.

AI also can be used to analyze information gathered through other technologies, such as satellite imagery. Take forced labor, a priority human rights issue for companies across sectors. Researchers in Brazil have used AI to identify forced labor at deforestation sites in the Amazon3. Although the reliance of legal and illegal deforestation on forced labor is well known, identifying deforestation sites rapidly enough for inspectors to reach them is immensely challenging. To address this challenge, researchers used satellite images of known areas of deforestation to train AI image-recognition tools.4 The algorithm learned visual markers of deforestation and used those markers to identify new deforestation sites from current satellite images, enabling inspectors to intervene more rapidly and effectively.

Key Human Rights Risks

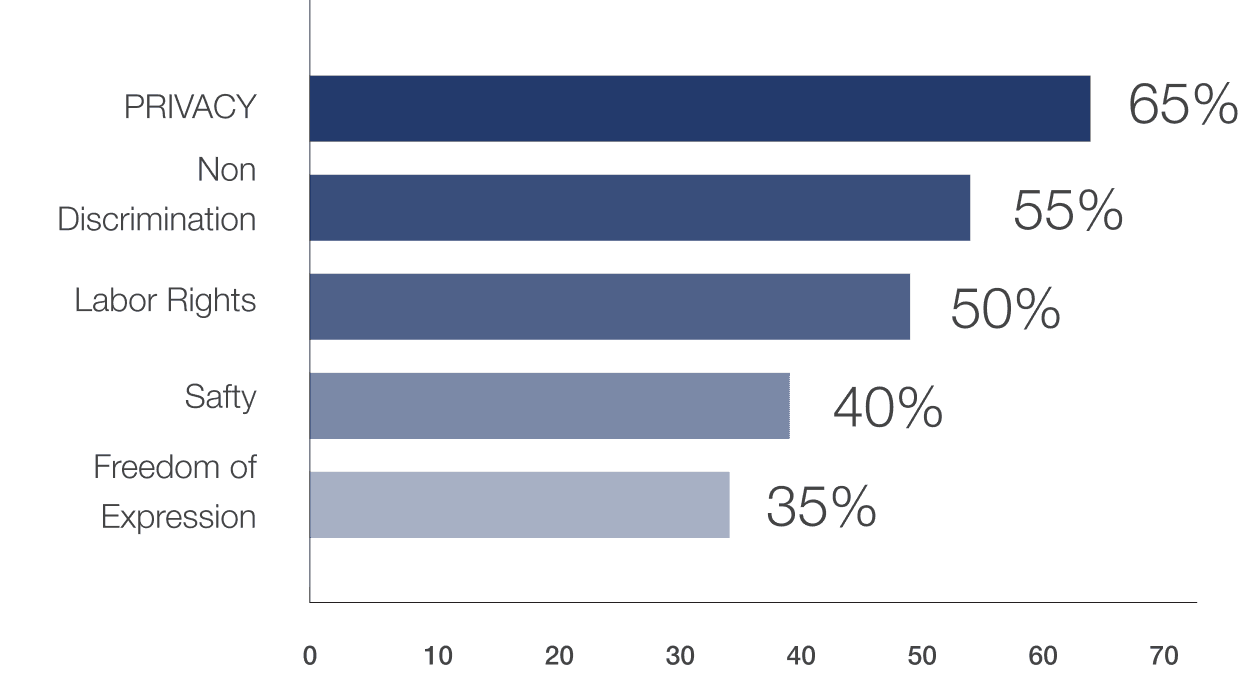

How AI is used may also shape human rights risks. These include most obviously the right to privacy, but they extend to an array of corollary and independent potential human rights harms.

Right to Privacy. The right to privacy is a “foundational right for a democratic society,”6 one integral to balancing power between governments and individuals.7 The right is almost instantly triggered when using AI systems because such systems require data, which often comes from people. The right to privacy is critical when considering AI use because violations of this right can easily lead to violations of other human rights, such as freedom of expression, freedom of association, freedom of movement, and the right to non-discrimination.

AI-related privacy violations can be intended or not. AI systems may infringe upon the right to privacy directly when they rely on deeply personal information obtained without a person’s consent or knowledge. Well-known examples include public authorities providing personal health information, collected with consent, to private third parties for use in an AI system, ostensibly to enable better medical decision-making. Patients knew their medical information was gathered for health care purposes, but did not know it would be given to a private third party or used in an AI system. On the other hand, an AI system might collect and use personal data in line with consent; if it then faces a data breach, however, the exposure of this personal, identifying information would impact the right to privacy.8

Freedom of Expression; Freedom of Association; Freedom of Movement; Arbitrary Arrest; Deprivation of Liberty; Non-Discrimination.

The rights to freedom of expression, association, and movement, and the rights against arbitrary arrest, unlawful deprivation of liberty and discrimination are all distinct rights. In the context of AI, the potential for violating them follows the same pathway. Flowing from infringements on privacy rights, biometric data and AI learning tools may be—and have been—used to identify and monitor individuals. That includes journalists, dissidents and their family members (infringement on freedom of expression). It also has been used to arbitrarily arrest individuals, prevent or deter people from joining together to protest or meet for political reasons (infringement on freedom of association), or prevent people from leaving or returning to a country (infringement on freedom of movement).

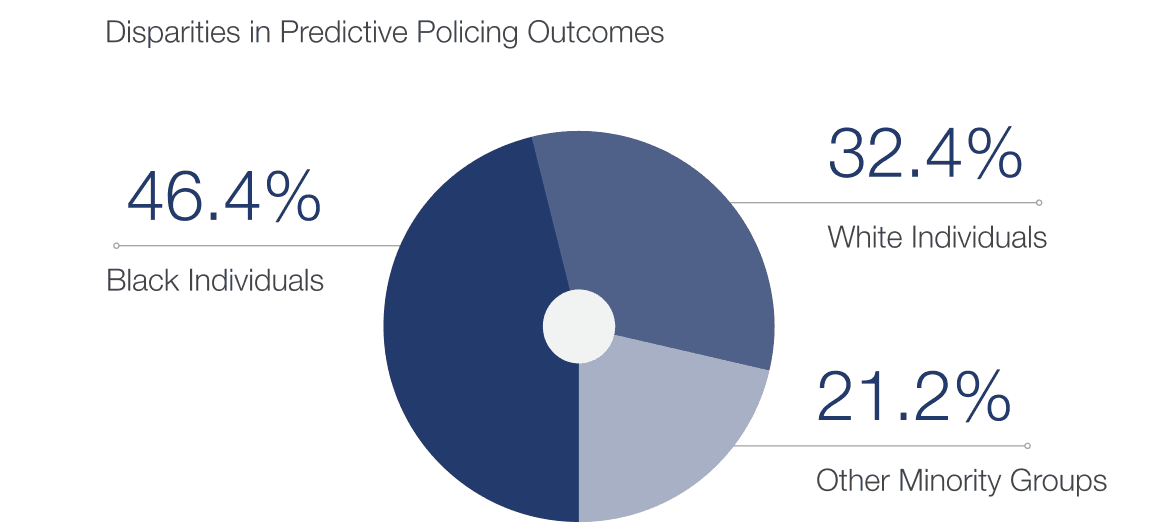

Similarly, AI has been used to distinguish between individuals using factors such as race, ethnicity, gender and age in a variety of manners. These range from targeted advertising, to considering job applications, access to health care and insurance, and arrests and detentions. The potential for discrimination is inherent in AI use, because AI depends on data; any bias present in the underlying data will necessarily be incorporated into the AI learning model. AI thus carries an inherent risk of introducing, replicating, or exacerbating biases.

Similarly, AI has been used to distinguish between individuals using factors such as race, ethnicity, gender and age in a variety of manners. These range from targeted advertising, to considering job applications, access to health care and insurance, and arrests and detentions. The potential for discrimination is inherent in AI use, because AI depends on data; any bias present in the underlying data will necessarily be incorporated into the AI learning model. AI thus carries an inherent risk of introducing, replicating, or exacerbating biases.

One example that clearly demonstrates the risk of AI-generated discrimination is the use of “predictive policing” tools. These tools typically combine historical and regional data collected by police departments and/or other governmental agencies with AI algorithms to make predictions and guide decision-making related to policing. These can be used positively, such as to detect potential terrorist activity, or negatively. For example, in the UK many police forces are using predictive policing tools to predict where certain types of crime are likely to occur and the likelihood of offenders to re-offend.9 Police forces then use this information to guide critical decisions e.g., where to conduct stop and search protocols or decisions related to an offender’s path forward, including whether they should be recommended for rehabilitation.10 While this can thwart crime, Amnesty International found that the use of predictive policing tools in the UK has led to increased stop-and-search protocols in specific neighborhoods.11 It also found that, in an eight-month period where a police force used predictive policing tools, it disproportionately used stop and search and force against racialized communities; stop and search of Black people was 3.6 times more than white people,and police used force against Black people almost four times as much as white people.12 In a similar vein, it has been reported that Chinese governmental authorities are using AI and facial recognition technologies to identify, monitor and track Uyghurs different cities throughout the country.

Conclusion

Applying a human-rights lens to AI use allows us to form a clearer picture of the impacts—both current and emerging—that AI technologies are having or may soon have on our lives. AI’s capabilities are vast and its applications are rapidly expanding across industries, governments, and communities. Just as AI brings transformative opportunities for innovation, efficiency, and economic growth, it also brings with it a wide and complex set of potential human rights consequences. These impacts are as diffuse and diverse as the technology’s business applications and benefits. While AI holds the power to vastly improve the enjoyment of human rights—such as through advancements in healthcare, accessibility, and education—it simultaneously carries the risk of undermining those same rights. The right to privacy, freedom of expression, non-discrimination, and access to remedy can all be compromised by poorly designed, unregulated, or opaque AI systems. Importantly, the harms are not always immediately visible; many of the risks emerge gradually, through data misuse, biased algorithms, surveillance, and automated decisions that lack transparency or accountability. As the development and deployment of AI technologies continue to accelerate, it is essential for organizations, businesses, and governments to proactively apply a human rights framework to their AI strategies. Doing so not only safeguards individuals and communities but also strengthens the long-term resilience, trustworthiness, and legitimacy of AI systems. Embedding human rights principles at every stage of the AI lifecycle—from design and development to deployment and oversight—is not just a matter of ethics or compliance; it is a strategic imperative for ensuring sustainable innovation in a world increasingly shaped by artificial intelligence.

Trending Insights

IDCA News